IT This page is translated in English

EDITORIAL by Ugo Soragni: “The relationship between the city, architecture and cinema has been the subject of countless attempts to retrace their historical evolution and analyse their connections and reciprocal intersections. Despite this, the vast range of critical angles and the use of analytical tools that have not always been comparable have not motivated a summary of the conclusions reached within their respective areas of specialisation.

This interpretative patchwork gave rise to a predominance of research in the anthropological and sociological fields which mainly focused, starting from the 1970s of the last century, on the deciphering of the language used by cinematography to describe urban clusters and landscapes, spaces and architecture, as well as roads and public transport networks. Many of these studies, often of great interest from a semiological point of view, have proved to be of limited use in the field of semantics regarding urban and architectural spaces (real or imaginary) photographed by cinema, albeit with the awareness they very often represent one of the most incisive ingredients of the cinematic narrative (sometimes prevailing over the drama itself) while, at the same time, bearing witness to poetic and creative ideas worthy of consideration. As has rightly been observed, the “great modern metropolises represent a logical background for the adventures of cinema, the material objectification of its founding moments. […] For cinema, the urban horizon is an intense set, a mobile picture of visual forces, dynamic figures and communicative forms. It is a score of visual and emotional potential, an array of attractions, heritage to be used and reworked […]”.

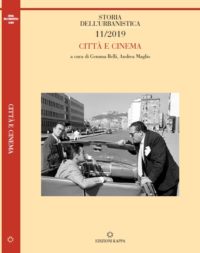

This issue of Storia dell’Urbanistica (Urbanist History), edited by Gemma Belli and Andrea Maglio, is testament to the magazine’s interest in addressing (without losing its critical and specialist identity, established over thirty-eight years of publications and in the evolution of three distinct series) some of the least studied branches of urban history, with a view to studying in-depth the links between the city and its representation in cinema. This choice that has made it possible to include, alongside input by some of our most authoritative and regular contributors, the outcomes of research carried out in this field by historians of Urban Planning and of Architecture, Media Studies scholars, and by architects. They are all united, within the differently structured approaches of their specialist areas, by an interest in shining a light on cinematography and its reflections (from its very beginnings to its most recent expressions) on their respective sectors of historiographic research or professional practice.[+]

Since the Venice Biennale in 1974 (Cinema città avanguardia: 1919-1939: a comparative exhibition between cinematic language and the problems of the city and modern architecture, 16 October – 15 November), the development in various studies on the relationship between the city and cinema highlights its tendency to nurture separately the historiography of urban and architectural space and that of the film scene. Even where the design of architecture and, we might add, the practice of decorative arts or industrial design have intertwined with the transposition of film or theatre – condensing, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, into the personas of the very same protagonists – the tendency of film criticism and historiography of the city to proceed along parallel routes has not disappeared, with only occasional opportunities to converge.

In support of this statement we can refer to some of the studies dedicated to Hans Poelzig (1869-1936), the famous designer of ‘gothic’ and expressionist architecture who was also often active in the field of theatrical and cinematographic scenography. Most of these, as well as the various exhibitions dedicated to him, are reluctant to acknowledge the importance of Poelzig’s scenography in his urban and architectural pathway, attaching to it instead a definition of professional digression of almost secondary significance.

Only very rarely has it been considered essential to correlate the study of his urban space models, his architectural and artistic sketches and his paintings with what have been positively defined as his Filmbauten (i.e. his ‘cinema buildings’), capable of visually dominating films such as ‘Der Golem wie er in die Welt kam’ (1920) or ‘Zur Chronik von Grieshuus’ (1923-24). At the same time, there exist justifiable reasons to believe that some of his projects and realizations may have inspired the visionary and disturbing urban landscapes of Fritz Lang’s masterpiece ‘Metropolis’ (1927), opening up new expressive horizons for the Viennese director’s creativity.

It is pertinent to analyse the reasons that have so far prevented Poelzig’s scenography, but also that of many other leading figures of German Expressionist Architecture, from being recognised as having a meaning that cannot be separated from that assigned to his designed or built architecture. The hypnotic fascination or feeling of anguished suspension conveyed to us by some of his real buildings (e.g. the Water Tank in Berlin [1910] or the Sulphuric Acid Production Plant in Luboń [1912]) provide, together with the alienating geometry of the places dedicated to hosting them, an exemplary case of a reversal in the conventional relationship between city and set design, where the former (usually considered the source of inspiration for the latter) seizes the illusionary rules of the set and feeds them into the architectural project. Thus, it maintains, if not total independence, at least sufficient autonomy from the demands of functionality, rationality and economy that any creative exercise must take into account when it docks with what is ‘real’ or, at least, ‘possible’. Poelzig’s most famous piece of architecture, the Grosses Schauspielhaus in Berlin (1918-19), disgracefully demolished in 1988, showed the absolute futility of any attempt to draw a dividing line between architectural research and scenic device, not only because of its cavernous interior lined with never-ending arrangements of ‘stalactites’ but perhaps even more so for the astonishing spaces – deformed and enveloping, hollowed out from sinuous openings – where the atria, distribution corridors and internal halls lie, punctuated by disturbing luminous ‘columns’, as the result of the combination of sculptural floral silhouettes and raking lights.

Written by Leonardi and Mangone respectively, the first two essays in this issue deal with comparable issues, which include references to Poelzig himself and other designers or theorists of German expressionist architecture: from Mendelsohn to Taut, from Finsterlin to Schöffler, Schloenbach & Jacobi. For some of them, the existence of solid cooperative relationships with some of the most innovative directors of the time was considered unquestionable.

Menna’s contribution deals with American documentary realism between the 1920s and 1940s, dedicated to some short films about industrialized metropolises which were destined to launch the city film genre, while a 1979 documentary by the planning expert and organizational analyst William H. Whyte about the relationship between New Yorkers and certain types of spaces for public use is the subject of the following essay by Baglione.

Belli focuses on the use of the cinematic medium by a contemporary architect such as Luigi Moretti, asserting that his shots of the Piazzale dell’Impero at Foro Italico in Rome between the 1950s and 1960s, for the architectural film ‘Formes du langage’, serve no descriptive purpose for his work but instead use its ‘abstract and metaphysical’ form to “substantiate his personal reflections […] on the topics of unity and plurality, as well as on the possible forms of human language”.

The interpretation of the urban and architectural settings of New York, used by Martin Scorsese in ‘The Age of Innocence’ (1993) and of Nice, used as the backdrop for countless films from the 1930s to the present day, are the subject of essays by Cardone and Pace. They underline, in the first case, the penetrative and descriptive capacity of Victorian society and, in the second, its mutability and adaptability to different, apparently irreconcilable narrative demands.

Angelucci deals with Wenders’ Berlin, described as “made up of heterogeneous parts, in strong contrast with each other, with a focus on the ratio between public and private places, between streets and buildings, in contrast to monumental spaces with more modest areas or livelier places like street markets”, while Scarnato concentrates on Barcelona, profoundly transformed by public works undertaken on the occasion of the 1992 Olympics and as such an ideal narrative background for contemporary cinema to spread ‘like propaganda’ the message of its own conquered modernity. The subject of Maglio’s piece is Francesco Rosi’s filmography, which uses views of Naples – starting with ‘La sfida’ (1958) and ending with ‘Le mani sulla città’ (1963) – to provide a dramatic representation of the devastation property and land speculation has had on the city, whilst underlining how the urbanist frames of these films, apparently inspired by a ‘neorealist spontaneity’, are in fact the result of carefully studied planning and testament to Rosi’s closeness to the world of design and architecture.

Greco’s essay is inspired by Ettore Scola’s film ‘Una giornata particolare’ (1977), which focuses on the bond established between a persecuted politician and the wife of an ardent fascist during Hitler’s visit to Rome on 6 May 1938. The event offered the opportunity to scrutinise the reasons behind the choices made (suspended between the celebration of Roman identity and the enhancement of the modern city) to outline the routes the German dictator would follow, which were designed to put forward the image of an “unreal imperial city, both spectacular and cinematic”. The contribution focuses, in particular, on the temporary installations devised by Alfredo Furiga, the famous Lombard painter, set designer and technician, which, from the use of scenic backdrops enhanced by night lighting, provided stunningly atmospheric effects. Finally, this issue concludes with a piece by Falsetti dedicated to the Roman district of Don Bosco, whose urban plan, constructed between 1931 and the mid-Fifties, can be easily compared to the nearby interventions on via Tuscolana of Muratori, De Renzi and Libera, giving birth to a novel example of working class ‘metaphysical’ spaces set in the heart of the Roman outskirts, “halfway between the Piacenza vision and the scenography of Cinecittà”.

The contents that we have briefly described here make this issue of Storia dell’Urbanistica one of the most original and stimulating in its most recent history, while one aspect that deserves to be highlighted concerns sources and, to a wider extent, the illustrative devices used in this issue.

The monographic nature of the studies, in addition to the wide use of publications, magazines and periodicals, has meant the selection and reproduction of single frames taken from Italian, European and American cinematic works, contributing to forming an iconographic collection of unprecedented wealth as well as significant and independent historical value.

U.S.

INDEX

Ugo Soragni

Editorial

Gemma Belli, Andrea Maglio

Introduction

THE CITY AND IMAGINATION

Walter Leonardi

Shadows and fog: urban imaginaries in German and French cinemas of the Twenties and Thirties

Fabio Mangone

Vienna and Munich, Berlin and Babylon: the background of Metropolis

THE DOCUMENTARY AS BOTH INVESTIGATION AND ARTISTIC EXPRESSION

Giovanni Menna

“Manhatta” versus Hollywood. New York in the non-fiction film between Avant-garde Cinema and Documentary Realism

Chiara Baglione

‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces’: film shooting as a tool for analysis in William H. Whyte’s research

Gemma Belli

“Formes du langage”: poetics of space in Luigi Moretti’s films

EUROPEAN CITIES, AMERICAN CITIES

Daniela Cardone

“Portrait of a City”: a film adaptation of the Victorian age

Sergio Pace

About Nice. The city and its inhabitants in moving images (1930-95)

Federica Angelucci

Wim Wenders: the sky above the city

Alessandro Scarnato

“Barcelona, make yourself up!”, cinema as a tool of urban redemption

THE ITALIAN CITY

Andrea Maglio

Before the “hands over the city”. Francesco Rosi’s The Challenge and the prelude of a failure

Antonella Greco

May 1938: The Parallel City of a A Special Day

Marco Falsetti

Popular Metaphysics: the Don Bosco district and the southern Roman suburbs between landscape and artifice

RESEARCH

Marco Cadinu

On the Trail of Farnesian Urbanism in Ales (Oristano), a New Bishopric of the Early Sixteenth Century

Giulia Beltramo

The Resistance between Lower Po and Infernotto Valleys in Piedmont: Territories and Settlements between History and Memory

Raffaella Russo Spena

The rediscovery of the spa tradition in contemporary age

Maria Clara Ghia

Bruno Zevi and his thought on Urbanism. From Ferrara as the first modern city to the visions on urbatecture