IT This page is translated in English

The winning book of 2019 Enrico Guidoni Award is now available:

Venice and Healthier Homes. Urban planning and premium housing (1891-1925)

by Alessandra Ferrighi

Series LapisLocus

2020 Ed. Steinhäuser Verlag – Wuppertal

IT This page is translated in English

From Introduction:

The 1884-85 cholera epidemic and the resulting enactment of a law For the Rehabilitation of the City of Naples (Per il risanamento della città di Napoli), constituted something of a pivotal moment in the urban history and history of the architecture of Italian cities, rendering them laboratories for the testing and application of new theories of rehabilitation and sanitisation.

The historic cities of the peninsula came to be viewed as unhealthy concentrations of disease-favouring phenomena, such as overcrowded housing and a lack of light and air circulation in narrow streets, and their configuration unsuitable to the improvement of residential and productive conditions, besides being incompatible with status ambitions and the ideas about hygiene being developed at that time – unless through drastic transformation. The administrations of the principal Italian urban centres were first and foremost called on to respond with ambitious planning projects to a continually expanding population’s demand for new housing. More specifically there was an urgent need to confront the problem of large areas of urban and residential degradation, characterised by slums lacking running – still less drinking – water, latrines or a sewage system, and by buildings dangerously compromised by damp infested walls. In the urban projects drafted in the last quarter of the 19th century we find on the one hand proposals involving the demolition – or ‘gutting’ – of whole sections of cities – associated with laying down new street plans and building complexes; on the other, extending the city by building entire new peripheral quarters in accordance with modern criteria of sanitary engineering. The new houses lining wide and orderly thoroughfares would impose regularity and dignity on finally bright and healthy neighbourhoods appropriate to the pretensions of the emerging social classes, from the professional and entrepreneurial bourgeoisie to the white-collar lower-middle class.[+]

It was the concrete expression of an ambitious political project spanning more than three decades, from 1891 to 1925, which offered private landlords an opportunity to upgrade their existing residential properties, and to construct new ones with the help of financial incentives proportionate to volume.

The project had its origins in a counterproposal to the Urban Upgrading Plans which had failed to gain government approval – plans which can be seen as embryonic attempts drafted ad hoc to tackle the pressing problems of a city in serious need of patching up. The blueprints underlying the various proposals for the ‘renewal’ of the city concerned chiefly the creation of new communication routes allowing more light and ventilation into narrow alleys by strategically demolishing old buildings. From the first scheme put forward in 1886 to a much modified one in 1889 was a laborious progression, and the approval of the latter led to a famous querelle between those wanting only to ‘preserve’ the city, who envisaged an indiscriminate wrecking ball disfiguring it, and those pressing for a healthier environment. Repeated revisions, suspensions and rejections on the part of higher authorities resulted in the appointment of a Joint Ministerial and Municipal Commission, chaired by Camillo Boito, to appraise the plans. Conflicting conclusions were again reached along the old lines: whether to preserve at all costs the picturesque character of the Lagoon city or to tackle its problems. The only items agreed on were to maintain the waterways by regular dredging, improve the sewage system, ban residential occupation of ground floor spaces, promote the construction of new houses and overhaul the existing stock – in practice deferring more comprehensive planning issues.

It was on the back of this decision to create more living units and upgrade existing ones, and while waiting for the Urban Upgrading Plan to be finally approved, that the idea of the Ten-year Premium took shape. After a detailed analysis of the increasing population of the city it was thought that building initiatives could well be left in private hands. The Selvatico administration concluded in fact that the only effective way of boosting the number of available living spaces was to encourage private landlords to build on undeveloped land and to extend their existing houses upwards. By encouraging private investment, it would be possible, with the aid of incentivising premiums per unit, to promote new initiatives, focusing on better equipped housing destined to be rented to the less well-off.

It was an opportunity to operate within the main body of the city, albeit in a piecemeal, here-a-bit there-a bit fashion, or in the wider municipality, wherever there was privately-owned free land, dilapidated and/or unhealthy houses to be demolished and rebuilt, or sound buildings that could be added to. The hope was that a gradual replacement of the residential estate would occur with a degree of spontaneity thanks to the incentives. The initiatives were called Premium Homes because once the houses were built and had been certified habitable, their private constructors could claim back, after ten years, a part of their investment under a contract agreed with the municipal authorities. The construction of new housing began on 11 September 1891 and continued, way beyond initial expectations, with a number of extensions, through to 31 December 1912. The policy was revived between 1922 and 1925, and achieved a gratifying response from the private sector, which resulted in a large number of apartments being made available through this kind of deferred financing. In total, in fact, more than two and a half thousand units were delivered, equipped with facilities that fully complied with the official sanitary regulations now considered necessary to a standard of living consonant with the requirements of a ‘modern’ city.

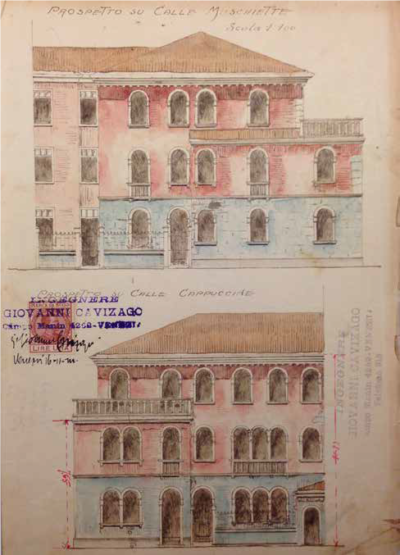

The Premium Homes policy has never been studied as a discrete phenomenon. When viewed in the round it offers a window on how Venice found room for the provision of affordable housing through private initiatives underwritten by public funding. The Premium houses transformed small sections of the city in two different ways: through ‘pastiche’ interventions linked to traditional methods of building within the pre-existing fabric, and by the construction of entirely new volumes which broke up or modified the dense urban environment characteristic of the Lagoon city. The hundred or so architects and engineers involved over this extended period adapted in their different ways to the ‘traditional’ context. The architectural vocabulary they deployed cannot be tied to any one style, but rather to a broad tradition of forms and materials. A Commissione all’ornato (Decoration Commission) became over the years increasingly active with regard to the external aspect of the facades, effectively controlling the overall appearance of the urban areas into which the new houses were inserted.

Undeniably these specific initiatives redrew the external aspect of some parts of the city and partially redefined its make-up, handing down to us a good part of the Venice we know today. This book looks at how and why these processes of replacement and transformation of the urban environment came about, locating them in the political, social and cultural framework of those decades.